Some things I’ve done, thought about, and seen in the first 12 days of a 17-day residency in Portland, OR.

—

On Saturday, I installed two pieces from The Eve Of… in the window project space at PDX Contemporary, with a little help from JZ, DH, Caitlin, and James. It’s viewable 24/7 at the corner of NW Flanders and NW 9th.

It’s a satellite of the larger exhibition at Portland ‘Pataphysical Society (‘Pata), which opens Thursday (First Thursdays) from 6-9pm, at NW Everett and NW 6th.

The exhibition at ‘Pata will include new works—four large pieces of handmade cotton rag paper, which I made with the tutelage of Jenn Woodward at the Pulp and Deckle paper making studio thanks to support from c3:initiative. The paper is created for display in the ‘Pata windows, which will also be viewable 24/7.

…

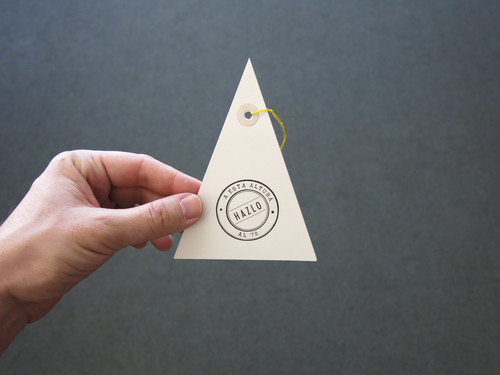

Make Things (Happen) PSU Assembly brochure page. Illustrations of activities by Kari Marboe & Erik Scollon, Piero Passacantando, and Tattfoo Tan.

Last Wednesday, I had a chat about Make Things (Happen) in PSU Assembly. It was sponsored by c3:initiative and located at Portland ‘Pataphysical Society. I invited Make Things (Happen) participating artists Lexa Walsh and Julie Perini to present their activity sheets and have a dialogue. Lexa asked me how I felt about shared authorship—I am interested in exploring it, and talked about the creative freedom I tried to offer artists, since I wasn’t able to offer remuneration. This spurred an audience member to ask Lexa and Julie what motivated them to participate. Lexa mentioned that this was a easy extension of an existing project, and Julie explained it’s hard to think of who would fund projects to fight white supremacy.

We also talked about if I’ve met resistance to my work about happiness, and I mentioned how much inspiration I take from Susan O’Malley‘s commitment to make art that is whole-heartedly positive. (At Harvester, I talked about how people can easily underestimate the amount of courage that making art about happiness can require.) Another person asked about where else I’d like to see this project, which reminded me of the last message I got from Susan:

I really think it would be amazing to see this project at the airport or library or DMV or city hall or some kind of public space…..

She was so smart about curation and public space. I should heed her words. These are just one more example of so many bits of wisdom she shared.

Thanks to everyone who attended, and who made it happen: Julie, Lexa, Shir, Erin, Josephine, David, Harrell, and many more.

…

I made paper before, once, in Nance O’Banion’s Bookmaking class as an undergrad. My memory of it pretty hazy, except for an image of the sheet collapsing as I unsuccessfully tried to “kiss” the wet paper pulp off the mold and onto the drying screen.

A few thoughts about paper making:

It’s technical, but much of it, like in printmaking, is by feel. You screw it up to know where it goes wrong, and then by experience feel when it’s right. For example, you figure out how much retention aid is enough, which you can feel in the softness of the water.

It’s physical. I made four 43×56″ sheets, each comprised of twelve sheets from a ~15×15″ mold. The water’s surface tension provides a good amount of resistance when you pull the mold. You sometimes have to lift and pour big buckets (30-40 pounds). A backache after the first day was all the reminder I needed to use my core and legs on subsequent days.

Oddly, I think having done vinyl signage helps. Though the materials couldn’t be more opposite in many ways—natural vs. plastic, historical or niche vs. ubiquitously modern—the processes share releasing a fragile sheet from one surface to another. It’s about timing and pressure.

It’s pretty magical. There’s no binder. The fibers just stick together. Because it’s very physical and intuitive, it’s a great process for finding flow. Jenn is a great teacher—very knowledgeable, patient, and no-stress. Pulp & Deckle‘s classes and private workshops are affordable. Recommended!

…

Time management. You might think that artists who are also art handlers will take less time to prepare for and install an exhibition. This is not necessarily true.

1. We can nerd out on details. I built a plinth for a work that usually sits on the ground, and a box for A/V that could just sit a shelf. I’m also sewing light blocks for ‘Pata’s clerestory windows and sheer window coverings to layer behind the paper.

2. It takes time. I underestimated how long it would take me to build boxes and pack my work to ship out here. Yet I work on crews where we do that for several days or weeks at a time. The scale of my work is smaller; but still, in this case, it included two large boxes the sizes of doors.

3. Because you never know when you’ll need to problem-solve. What can go wrong when you’re traveling, using local sources, unfamiliar tools, and new spaces? The patience and generosity of friends and strangers go a long way.

…

Bathing in the afterglow of the Postcards from America opening at Newspace Center for Photography; it was pretty cool to see dudely big-deals like Alec Soth and Jim Goldberg mixing it up with local subjects (a retiree, a girl named Cherish, a physical therapist who served vets, an advocate for Iraqi refugees) and PSU Social Practice students. The event was part of PSU Assembly. Susan Meiselas‘ project to raise the visibility of VOZ, a worker-led organization to empower immigrant workers is a smart, worthy way to use photography in social practice; limited edition screenprint posters are available to raise funds for printing. It’s super cute and signed by the Portland Postcards from America photogs. I was tempted. I previously thought Magnum was just a hotshot agency, but in a recent talk at Portland Art Museum, they explained that it’s a co-op run by photographers for photographers, and had to find new ways to support the work they want to do.

…

Yale Union/YU Contemporary‘s new exhibition by Willem Oorebeek. We were only there for a few minutes between engagements, and my largest impressions are of the space (a huge renovated industrial space not unlike Mass MOCA or DIA:Beacon, with beautiful light) and the architect-made exhibition design (2×4 framing on 12″ centers, very selectively sheathed). There were reproductions from magazines, and sheets of glass over rubber flooring with round nubs intended to read as pixels, though I thought of LEDs. There were black-on-black prints (black lithographic prints over a variety of mediums) that had optical or durational effects—you had to stand right in front of them to see them, which was engaging in how it forced an intimate relationship with the image within a massive space.

…

Woodwork. Borrowed tools from a suspension-tree-house maker named Devan. A 12″ compound miter saw, Skil saw, and compressor and nailer (yes!). Nice blades, smooth sailing. I forgot to pick up clamps, though, so I nailed a 1×2 as a guide wherever I needed it. It hit 92ºF and the patio umbrella was a savior.