_____ness, overexamined.

Longtime New Yorkers, including Martha Rosler, like to point out how suburbanized New York City has become. However, I could argue that, as real New Yorkers, they do not truly know suburbia. I thought about this as I stepped off the SFO-originating BART and into the slow, foggy town of my teenage years, where, over the coming days, I would complain about how the Home Depot’s layout is backwards from its usual lumber-on-the-right floor plan, and, for even the most middling of needs, visit Target at a mall whose property line would encompass two subway stops on the N/Q. No stranger in a strange land, I’m a prodigal daughter in an ur-burb. I mull “basic culture”—the concept, terminology, and usage, and all the classism and cultural elitism it entails—while consuming it too.

With this in mind, Tram 3 struck me as extremely _____, in multiple ways. Here, rather than a symbol of purity, it’s a non-color, a normative default, nothingness. It pervades the works with the angst of pointlessness.

For Tram 3, the Wattis is a large, airy, sky-lit cube immaculately painted in matte, cool _____. Nary a patch glinted. Several oversized, oversimplified human-like cutouts populate the space. They’re simply constructed from steel plates, but are painted so matte and so _____ that they could well be Sintra (a rigid foam board). Casually taped on them are quick sketches of portraits on _____ paper, drawn as if the artist was short on graphite and time. On the walls are similar drawings of trams and tram riders. They’re framed but unglazed. The whole space is luminous with soft, reflected light. Even the track incandescent lighting approximates ambient fluorescents.

In a cavernous neighboring space, the artist’s video, Die Aap van Bloemfontein [The Ape from Bloemfontein] (2015) plays. Or, rather, the media advances. It’s a spectacle of inaction, a series of painfully long shots of tableaux in which actors imitate motionlessness. The actors are all _____. They are shot under hot lights, in unflattering, tight close-ups. Moles glisten. Crooked teeth are bared. A narrator’s voiceover describes transformations of objects into subjects and back. Rather than magical, it’s passively futile. Nothing happens, acutely. It’s not liberating Zen; it’s oppressive sameness. It’s monolithic culture, Northern European social order, and suburban predictability. It’s ennui born of (first-world) boredom. Sartre flat-packed in IKEA.

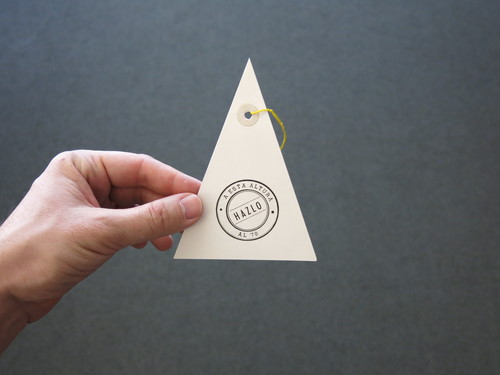

The exhibition signage is black text in Times Roman, a signature that Wattis director Anthony Huberman imported with him from the Artist’s Institute in NYC. Simple, black-and-___, and open is a quietly loud differentiation from predecessor Jens Hoffman, who with graphic designer Jon Sueda gave each exhibition assertive identities via color, typography, and architectural interventions. Under Huberman’s lead, the Wattis’ collateral has become restrained and cerebral. The website features no images, as if to say that art is not objects and visuals, but a series of open-ended ideas and exercises best experienced temporally and ephemerally. Thankfully, the exhibition brochure is written with concision and wit. While it ascribes absurdism to de Gruyter’s and Thys’ work, I didn’t see this lightness. If there is humor, it’s only black.

Through April 18

Jos de Gruyter & Harald Thys: Tram 3

Wattis Institute

San Francisco, CA