Last weekend I attended the International Positive Psychology Association’s Second World Congress on Positive Psychology in Philadelphia, PA, with the support of a Travel and Study Grant from the Jerome Foundation. It was an invigorating experience. I gained new concepts, an inspired list of books to read, and a clearer understanding of this growing field.

Positive psychology is a new realm; I’ve encountered skepticism of it based on its name only. But the conference (which I’ll call ‘IPPA,’ pronounced “IH-pah”) featured rigorous empirical researchers and practitioners across clinical psychology, education, business, and the humanities. With 1,200 whip-smart attendees from 62 countries, I felt as though I was part of an emergent domain that will revolutionize psychology as well as culture. I’ve been reading books about positive psychology since 2009; IPPA made me excited to learn more and help advance the field as it intersects with the arts and humanities.

—

What is positive psychology? Perhaps this is best explained via the words of its founding psychologists, Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (2000), as quoted by Robert Vallerand:

“Psychology should document how people’s lives can be most worth living.”

To paraphrase James Pawelski, IPPA President as well as the Director of Education and Senior Scholar at the Masters of Applied Positive Psychology program at UPenn, one of the leading centers of research and scholarship:

Positive psychology is not merely a psychology for sunny days. It is also a psychology for rainy days…. [As a young person witnessing the aftermath of the recent terrorist acts in Norway said,] ‘If one man can create so much hate and death, how much good can we create together?’

I think it was also Pawelski, in discussing the positive turn in humanities, who expressed that

We see positive psychology as balancing (negative) psychology

which for the 20th century has been fixated on trauma, illness, and pathology. As in physical medicine, it is high time to expand beyond treatment towards wellbeing. As Chris Peterson put it:

“Health is more than the absence of illness”

and so too, psychological wellbeing is more than the absence of pathology. The positive psychology view according to Martin Seligman is that

People are not driven by the past, but can be drawn to the future.

Again, Pawelski:

Rather than seeing the positive as simplistic, positive psychology makes the positive more complex.

—

What I looked forward to. Many of my drawings in the Positive Signs series, as well as some concepts in my essays on Art Practical, were inspired by Martin Seligman’s Learned Optimism and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Creativity. During my residency at Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild immediately preceding IPPA, I read Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. So I was very excited to hear Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi speak.

Seligman (left) and Csikszentmihalyi (right) are named IPPA Fellows.

I was also excited to meet potential partners, especially those whose work intersects with the arts. I suspect that principles of positive psychology can be useful for contemporary artists by informing:

•processes, by becoming aware of flow activities;

•artwork, via increased understanding of relationships created in the art viewing experience and new theories of phenomenology; and

•attitudes, especially in regards to experiencing career setbacks and successes.

—

Highlights. I was very excited about:

Clearer definitions. University of Illinois researcher Ed Diener identified

preconditions of happiness as optimism, positive experiences, and lack of negative affect.

Gallup Scientist in Residence Shane Lopez pinpoints hope.

“Hope is goal-directed thinking (goals thinking) in which people perceive that they can produce routes to desired goals (pathways thinking) and the requisite motivation to use those routes (agency thinking).

Hope — The ideas and energy we have for the future.

High hope people believe that the future will be better than the present and that they have the power to make it so.”

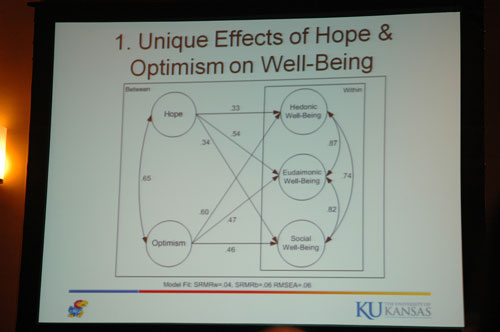

Matt Gallagher, a clinical psychology researcher at the University of Kansas, distinguishes between hope and optimism:

Hope (Snyder) — Agency and pathways towards goals

Optimism (Scheier & Carver) — Globalized positive/negative expectancies

Emphasis on personal agency [is the] crucial difference

He also explained the difference thusly:

When you mash optimism and self-efficacy together, you get hope.

Erica Chadwick, PhD candidate from the Victoria University of Wellington, shared this definition of savoring from Fred B. Byrant and Joseph Veroff (2007):

If a savoring process is elicited when a positive emotion is experienced, then savoring could well be the mediating mechanism through which a person’s cognitive repertoire is expanded when a positive emotion is experienced. Furthermore, when people savor, they often broaden the range of feelings they can have and contexts in which these feelings can occur.

Happiness is not frivolous. Hope can’t wait.

Lopez’s Gallup studies revealed that

Hope, engagement, and wellbeing do not correlate to income.

Clearly this is not an argument against equity, but a call to foster hope without delay. That’s because, as Lopez pointed out,

“When we link ourselves to the future, we behave better today.”

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1943) is a fundamental psychology concept visually represented as a pyramid. The idea is that basic needs must be met first, and in order of importance, with self-actualization as the pinnacle—and endmost—need.

At IPPA, Diener argued that

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs can be addressed at all levels, not necessarily in the order Maslow suggested.

Ed Diener's revision of Maslow's hierarchy of needs, with basic needs side-by-side with psychological needs.

Edward Deci, who studies self-determination theory, focused on

three basic human needs: the need to express competence, autonomy, and relatedness, which can be intrinsic, extrinsic, or emotionally motivated. Extrinsic motivations can actually undermine intrinsic motivations for engaging activities.

Edward Deci's Self-Determination Theory describes three basic psychological needs. Competence is the sense of effectance and confidence in ones's context. Autonomy is to behave in accord with abiding vaules and interests, and engage actions that would be relatively self-endorsed. Relatedness is feeling cared for, connected to, and having a sense of belonging with others.

I especially appreciated Deci’s point that

Autonomy does not mean complete independence; you can be autonomously dependent

because that points to how artists can be autonomous and forge their own paths with the support and encouragement of their peers.

This sentiment was echoed by Karen Skerrett, who studies qualities of resilience in couple relationships:

Resilience is not self-sufficiency.

Deci added that

To foster greater internalization, create social contexts that allow people to feel competent, autonomous, and related. But it must fit with who people are

Which seems like a worthwhile consideration for artists developing participatory and relational projects.

Diener also identified,

“The number one predictor of enjoyment: ‘I learned new things, and I got to use my new skills today.’

In advance of a positive criticality. Since even my wholly optimistic work can inspire projections of skepticism, I was especially keen to hear Pawelski share Csikszentmihalyi’s opinion that

Positive psychology is a metaphysical orientation towards the positive. In other words, the positive is just as real as the negative.

Dan Moores illustrated this with a humorous talk called Ecstatic Poetry and the Limits of Suspicion. In it, he conveyed

we have a hermeneutics [study of interpretation] of suspicion (Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud), while lacking a hermeneutics of affirmation.

Such a hermeneutics disserves

“The ecstatic poetic tradition [which] connects many cultures and reaches across vast stretches of time. It represents a positive affirmation of the values of happiness, human connections, festivities, and relatedness to transcendent sources of meaning. The tradition contains countless poems depicting peak states of being and positive, life-affirming emotions, such as serenity, awe, wonder, rapture, joy, gratitude, and love. Such poetry is written in praise of the goodness of life, the abundance of nature, and the intimate interrelation of the whole cosmos.”

Unsurprisingly, Moores shared a Romantic poem. This spurred a sense that contemporary art trends that revisit Romanticism and Transcendentalism (the “New Sincerity”) may find inspiration in this intersection of positive psychology and humanities, if the scientific approach isn’t too much at odds with the intuitive nature of such artmaking.

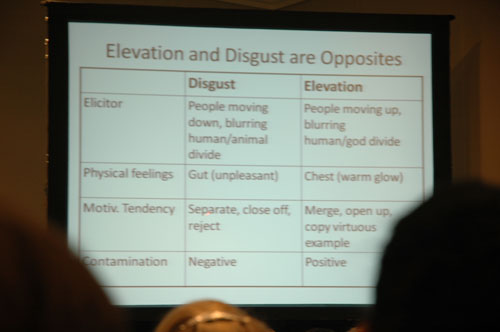

Elevation and awe. Jonathan Haidt, who studies moral political psychology, presented research

on emotion and elevation, correlating ‘up’ with altruism and admiration

Jonathan Haidt's chart showing how Elevation and Disgust are Opposites. People moving up blurs the human/animal divide, stirs unpleasant physical feelings in the gut, and motivates people to separate, close off, and reject, so is negative. People moving up blurs the human/god divide, providing a warm glow in the chest, and motivates toward merging, opening up, and copying virtuous example, and so is positive.

It’s similar to the up-down cognitive metaphors in Lakoff/Johnson’s linguistics, which I diagrammed in Positive Sign #24.

Christine Wong Yap, Positive Sign #24 (Conceptual Metaphors), 2011; glitter and neon pen on gridded vellum; 8.5 × 11 in./21.5 × 28 cm. Source: blog.sfmoma.org.

Veronika Huta, who studies awe, inspiration, and transcendence at the University of Ottowa, independently confirmed that

Elevation is correlated with, and is an indicator of, virtuous, pro-social behavior.

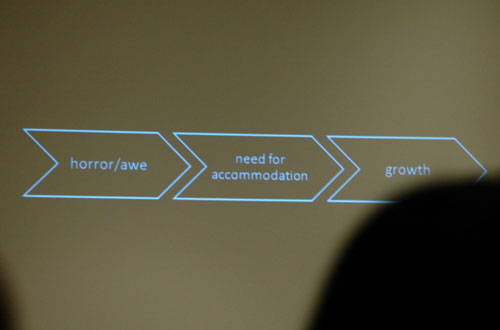

Connecting neo-Romantic art and studies of awe was UPenn graduate student Ann Marie Roepke’s diagram relating horror and awe, similar to the 19th century view of the sublime.

Slide by Anne Marie Roepke showing horrow/awe to need for accommodation to growth.

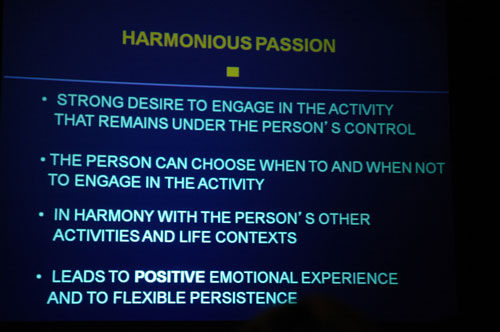

Passion. Robert Vallerand, from the University of Montreal, studies obsessive and harmonious passion.

Robert Vallerand describes harmonious passion as a strong desire to engage in the activity that remains under the person's control. The person can choose when to and when not to engage in the activity. It is in harmony with the person's other activities and life contexts, and it leads to positive emotional experience and to flexible persistence.

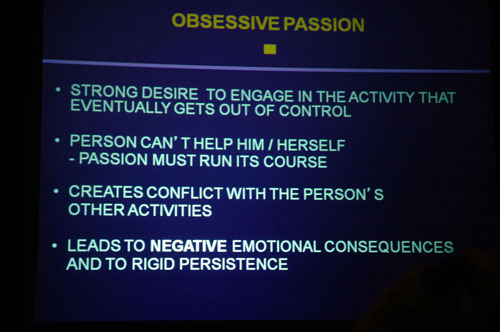

Vallerand describes obsessive passion as a strong desire to engage in the activity that eventually gets out of control. The person can't help him or herself; the passion must run its course. It creates conflict with the person's other activities, and leads to negative emotional consequences and to rigid persistence.

There’s a clear analogy to the arts here, where artists may develop a detrimental obsessive passion driven by extrinsic motivators, rather than a harmonious passion fueled by intrinsic motivation that leads towards increased subjective wellbeing.

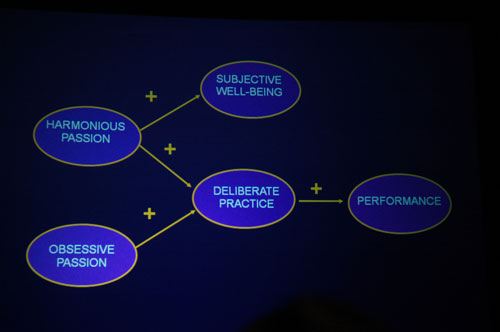

Vallerand found that obsessive passion and harmonious passion can both lead to deliberate practice and performance, but only harmonious passion will include enhanced subjective wellbeing.

Since I think emerging artists can put pressure themselves to see extrinsic rewards to their progress, Vallerand’s final message seems especially relevant.

Vallerand's take home messages: Try to cultivate harmonious passion for one activity. Take the activity seriously without taking yourself seriously. Include other fun activities in your life. Understand the functionality of obsessive passion. Learn from setbacks, improve and grow within the activity.

—

Information graphics. What follows is a sampling of visuals which appealed to me.

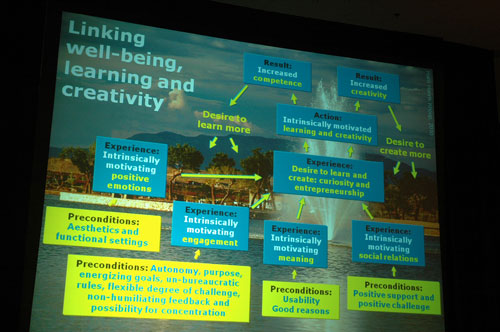

Hans Henrik Knoop's flow chart linking wellbeing, learning, and creativity, delightfully overlaid on a fountain.

Neural synchrony imaged by Stephens, Silbert and Hasson, displayed in a talk by Barbara Friedrickson.

Sara L. Trescott presented a poster entitled Pain and Happiness: A Shifting Mathematical and Psychological Paradigm.

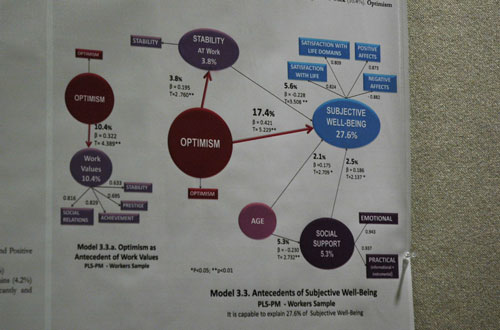

The most frequently presented graphic seemed to be a flow chart whose correlations are represented in nominal tenths or hundredths, rather than the visual hierarchies I would have preferred. It might well be a data-minded scientific idiom. Perhaps visual representation would be misconstrued as non-empirical shorthand.

I believe this is Lucia Helena Walendy De Freitas' poster on The Influence of Optimism on Subjective Wellbeing: A Study Based on College Students and Workers Samples.

Bee Teng Lim's Powerpoint flow chart showing the impact of amplifying savoring.

These graphics, indeed, the positive psychology endeavor as a whole—recall a passage from Alain de Botton’s The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work, in which the author responds to an engineer’s algebraic formula:

“I was struck by how impoverished ordinary language can be by contrast, requiring its user to arrange inordinate numbers of words in tottering and unstable piles in order to communicate meanings more infinitely more basic than anything related to an electrical network. I found myself wishing that the rest of mankind would follow the engineers’ example and agree on a series of symbols which could point incontrovertibly to certain elusive, vaporous and often painful psychological states—a code which might help us feel less tongue-tied and less lonely, and enable us to resolve arguments with swift and silent exchanges of equations.”

Two projects deserve special recognition for employing terrific graphic design. Both were large-scale public initiatives promoting wellbeing, thus the success of the endeavors was dependent on accessible design and copywriting.

Nic Marks discussed a project with new economics foundation promoting wellbeing in London.

Nic Marks presented Do-It-Yourself Happiness, a Well London project.

Plus, Marks conducted a drawing exercise in which workshop attendees drew each other without looking at their papers, which enacted the five steps the public initiative promoted. I loved the exercise, as participants’ responses were immediate, hilarious, and relational.

Participant's blind portrait of another participant.

Chris Peterson and Nansook Park, both from the University of Michigan, shared their ___ Makes Life Worth Living campaign, a university-wide year theme. Students wore t-shirts with the blanks filled in.

—

Conference photos. And inspired by Richard Baker’s quiet and stirring photographs in Alain de Botton’s The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work, I clicked a few images documenting the visual vocabulary of the conference.

Gina Haines' poster on positive psychology and phenomenology featured a foil mirror.