How I know what I know about social practice.

I’m collaborating on a participatory project and advising a social practice grad student right now. It’s made me think about how I know what I know, and why I approach and shape projects the way I do. I didn’t major in social practice—I majored in printmaking, working with Ted Purves as a thesis advisor. Though I sometimes wonder what I might’ve learned had I majored in social practice, it’s gratifying to come across references that are intellectually stimulating because they resonate which my existing practice.

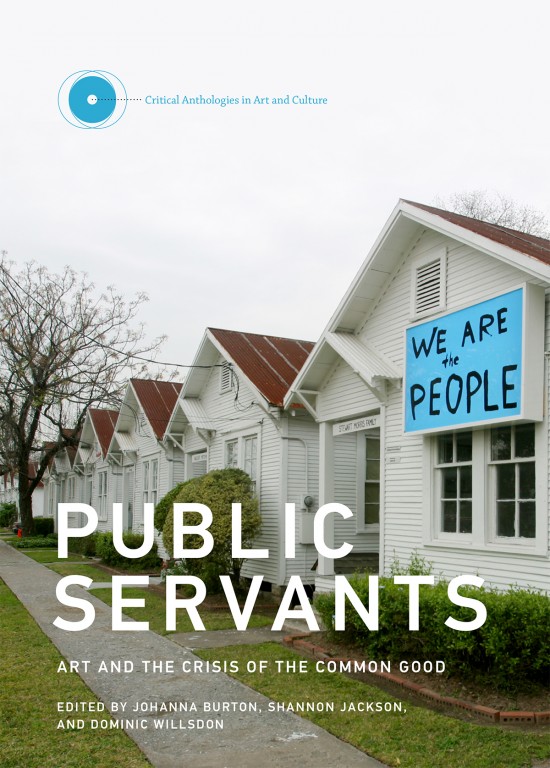

Public Servants: Art and the Crisis of the Common Good, edited by Johanna Burton, Shannon Jackson and Dominic Willsdon. // Source: MITPress.MIT.edu.

The dialogue spurred by Ben Davis’ “A Critique of Social Practice Art: What Does It Mean to Be a Political Artist?” still poses fresh, relevant questions. Originally published in 2013 on an activist website, Davis’ critique generated a remarkably thoughtful debate on Facebook between Deborah Fisher (director of A Blade of Grass), Nato Thompson (then artistic director of Creative Time), Tom Finklepearl (NYC Commissioner, Department of Cultural Affairs), artist Rick Lowe of Project Row Houses, and many others who have dedicated their life’s work to socially-engaged art or social practice.

This debate was reprinted in Public Servants: Art and the Crisis of the Common Good, edited by Johanna Burton, Shannon Jackson and Dominic Willsdon (MIT Press, 2016). [That an MIT Press book would reprint a Facebook thread is sort of amazing.]

The debate spans:

- Weighing the political efficacy of social practice projects versus their symbolic power. Davis provocatively asks if social practice projects are a distraction from activism. Many respond by defending the importance of the symbolic power of art, and the “need for a poetics of social change” (Fisher).

- How socially-engaged projects relate to power, privilege, appropriation, and exploitation.

- Projects should be guided by ethics, specifically, treating people with care and respect and not being co-opted by power it intends to reshape (Fisher).

- Be wary of when the image of social consciousness is used to gain social capital (Thompson) [in other words, “performative wokeness“].

- Does a project help or harm? Is it merely tolerated? (Fisher)

- Socially-engaged art is not inherently good. Likewise, neither is creative place-making. Indeed, developers use artists to create “vibrancy,” rather than critically-engaged projects, and resources can be diverted away (Lowe).

- Social practitioners shouldn’t get too “self-satisfied” (Davis) because social practice cannot replace activism and organizing. [I would argue that no one person or role builds a people’s movement. It wasn’t explicit but the solutions hinted at seemed Alinskyist.] Davis says that artists have an important role to play in political struggle, but they don’t have special access to political wisdom. [I think any artist who’s read any writing by Davis or Gregory Sholette knows that political education is a serious endeavor distinct from art practice.]

- How to assess socially-engaged art, such as through ‘participatory action research’ and ‘collaborative action research’ and involving stakeholders (Elizabeth Grady). While you don’t want to rely only on artist’s first-person accounts, you can define efficacy first in terms of artists’ goals (Fisher).

- The impossibility of not being co-opted by capitalism and the possibility of momentary acts of resistance. Davis cites Rosa Luxemburg on how many small victories and tiny inspiring acts are needed in the building of a movement.

Some thoughts expressed exceptionally eloquently:

“A great artwork embraces paradox and contains multiple, sometimes contradictory, truths. …this quality… gives a great socially-engaged art project the ability to reframe, reshape or, for a moment, redistribute power.”

—Deborah Fisher

Fisher also described the Rolling Jubilee as:

“a gesture that punches through that which oppresses us in a way that is infectious and influential because of its profound elegance.”

This “profound elegance” is my primary criteria for successful social practices: how they balance relations and forms, through process and ephemera. The projects I most admire are ethical and non-exploitative. They honor participants’ dignity, agency, intelligence, and time. And they are enticing and welcoming.

At the same time that I want to hold artists accountable to high standards, I also think it’s important to let artists be creative, experiment, and fail. The rules and forms of social practice aren’t codified. We don’t need any more predictable art or social relations.

The Public Servants editors wisely end the chapter with a passage from Louisa MacCall, co-director of Artists in Context, which connects artists and non-artists to collaborate on addressing issues. When I read MacCall’s words, it was like she was describing the goals in my practice (emphasis mine):

“What if we consider artists as researchers who can design, experiment, fail, innovate, and contribute to society’s knowledge production?

“To regain our sense of connection, agency, and empathy—which are vital to a just and sustainable society—we must consider the different kinds of questions and outcomes artists are proposing as indispensable to our systems of knowledge production.”

I’ll keep diving into Public Servants.

I’m also looking forward to the US Department of Arts and Culture’s “Citizen Artist Salon: Art & Well-Being” this Wednesday which connects social justice and wellbeing.

“how social justice is a chief indicator of individual and community health; how art can nurture well-being; and what you can do to build a culture of health.”