Art, through a cold-induced fog.

Post-Eve Of… and pre-day-job-slam, I saw an artist-organized show in Newark, and subjected myself and GQ to the pain and pleasure of the MoMA. I have a cold that’s largely fueled by brainpower, so pardon if these impressions lean extra impressionistic.

—

Julie Nymann, Shreds of Laughter, 2014, 0:06:00, 9:16 HD, Vertical projection, stereo, wood shavings // Source: julienymann.com.

Through 19, 2014

No More Place

93 Market Street, Newark, NJ

Gallery hours: M-F 1-5; Sat & Sun 3-6

No More Place is an artist-organized group show featuring 20 participants who met in the Bronx Museum of the Arts’ Artists in the Marketplace program. I made the trek to Newark to support my colleagues’ grassroots efforts,* and was impressed with several new works on view.

There’s lots of strong work displayed over two large, open floors. It ranges from painting, sculpture, video, installation, and photography, to site-specific wall drawings (notably, Margaret Inga Wiatrowski’s window project engaged Newark history, and she seemed to make a strong personal connection with passersby).

Some of the works that left the most lasting impressions on me were videos. Catherine Telford-Keogh’s video of an act of extreme intimacy—eyeball-to-eyeball contact—will haunt the squeamish. Tatiana Istomina’s edit of a film of a Ronald Reagan speech didn’t include any words by the former president. He’s shown pausing, sighing, and breathing. Yet the audience reactions sounded occasionally, at a slightly-above-comfortable volume. Compellingly, the absences became provocative.

Julie Nymann’s video installation, Shreds of Laughter (2014) was shot as a bird’s eye view of the artist hand-planing a wood panel, but the surface of the wood was replaced with a video portrait of the artist laughing (though it also seemed like crying at times). As she scraped, she obliterated her own image. The projection was in a stairwell covered in wood shavings. Viewing it offered time for reflection: Was she silencing the ego? Overcoming emotions? Facing mortality? Nymann’s technical proficiency as both a performance and video artist made it engaging, while the gesture’s poetry was satisfying.

Also mesmerizing were David Gregory Wallace’s 3-D animation using drone footage (it’s under the stairs; don’t miss it), and Brian Zegeer’s installation using macramé, bicycle tires, wallpaper, and audio. This latter work seemed the most successful in negotiating the second floor’s quirky architecture, specifically the angled mirrors chamfering the space—vestiges of once-ubiquitous retail surveillance preceding our security camera-studded present.

[*As in The Eve Of…, the artists had to change over a rough space, using time, money, and skills to make an exhibition out of an idea. I heard that Tasha Lewis took on much of the leadership and responsibility for the install. It’s challenging for one person to assume so much responsibility; but it’s also hard to know how groups of artists can distribute labor more evenly. I’ve been thinking about this a lot: how to step up and step back, and how groups of individuals equitably contribute.

I also enjoyed the chance to check out Newark’s art scene. It’s easy for New Yorkers to complain about the same old same-old; it’s harder to get off the beaten path. Crying about how you can’t see art at openings? Then make the extra effort to frequent spaces where you won’t be “seen” or “run in to” “people.”

The Newark scene seems anchored by Gallery Aferro, which made No More Place possible. In a cluster of galleries on one block, there were window interventions, a community-based art exhibition, and an exhibition of works examining queer African identity. One gallery was selling Newark-pride T-shirts, including an 80s retro overall print on a tiny crop top. It felt buoyant. Looks that sassy don’t just happen anywhere.]

—

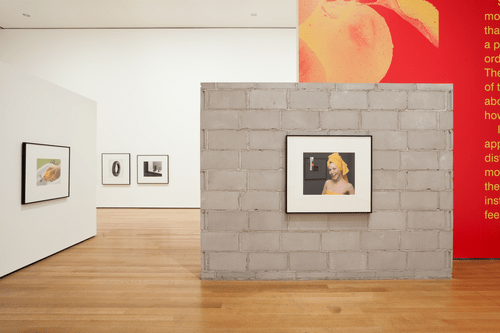

Installation view of Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness, The Museum of Modern Art, 2014. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar. © The Museum of Modern Art, New York // Source: moma.org.

Through November 2

Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness

MoMA

I don’t know much about Williams, but what I take away from this show is that he’s fearless. The list of things he’s not afraid of include:

- boring subjects

- a seemingly-random range of subjects

- shooting in an almost-no-style style, reminiscent of any product shot ever

- hanging things on a exaggeratedly low (48″?) centerline

- showing only modest-sized (16×24″) prints in one’s MoMA retrospective

- not pandering to audiences by:

- evincing technique and craft

- including didactic texts in the galleries

- including a curatorial statement in the foyer

- displaying what text there was inscrutably, running off walls like pages of RayGun Magazine, and set in McDonald’s-like yellow on red.

Indeed, it seemed like most visitors I saw didn’t “get” the Williams show—most were walking through too fast, like flicking pages in a waiting room magazine. Without wall labels to anchor the images in information, they hadn’t any signposts to orient themselves. Is that a fault of viewers or curators? Is it a sign of a poor experience, or an unusual challenge? Does everything have to be contextualized?

—

Robert Gober (American, born 1954). Untitled Leg. 1989–90. Beeswax, cotton, wood, leather, human hair, 11 3/8 x 7 3/4 x 20″ (28.9 x 19.7 x 50.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Dannheiser Foundation. © 2014 Robert Gober // Source: moma.org.

Through January 18, 2015

Robert Gober: The Heart Is Not a Metaphor

MoMA

The 2009 Charles Burchfield survey curated by Robert Gober blew me away, and made me re-consider this mysterious sculptor of sinks and white collar, White guy legs. Rumors of installation feats were also going around the art handler gossip mill, so I was really looking forward to this retrospective. It exceeded my expectations.

Yes, there are sinks.

They are made of wood, wire mesh, plaster, and paint. When I’ve seen them before, they looked like regular old sinks. But maybe because I am a bit more familiar with the laboriousness of actually sculpting something, or maybe because the lighting’s better, or maybe because I looked harder, the handmade-ness of these works came through better.

Yes, there are legs.

They stick out of walls, wear leather dress shoes, long grey socks, and slacks. They also wear tennis shoes and no pants. They also are burrowed out with drains, or project candles. They get whiter and whiter until they seem no longer attempt to simulate flesh tones. They evolve to include children’s legs, taking a hyperrealist-surrealist gesture further into nightmarish territories.

And, there are prints.

But they look like scraps of paper: ads, clippings, receipts. And yet they are intaglio prints, wood engravings, and unbelievably, potato prints. The absurdist rendering of one disposable thing in a labor-intensive fine art medium reminded me of works I wanted to make in grad school, which I had neither the mastery nor patience to see through.

And there was much more.

Many rooms were completely wallpapered in custom prints. Some were fun, some were trippy. There was a church-like installation, with two similar but significantly different peephole-like views. There were two rooms generously dedicated to showing other artists (no artist is an island). There were oddly rough sketches and wacky oil paintings that were strange to square against such precise realism and craftsmanship. There was, in fact, an installation feat worthy of even jaded art handlers’ gushing, and though most people had an “Oh, cool!” reaction, they missed crucial elements seen from only one view.

Throughout, Gober seems to be saying, “Look again!” Yet there were times when I also thought about Felix Gonzales-Torres, Tom Friedman, and Marcel Duchamp. The verdict? Definitely worth a visit. Be prepared to be both unnerved and amazed.

—

Exhibition design challenge: Compare and contrast the use of labels in the Williams show (where they were absent) and Gober show (they were informative, revealing disguised techniques and media, and ultimately, more understanding of Gober’s craft and interests).